Master SOLID principles and Domain-Driven Design to write software that doesn’t turn into a maintenance nightmare.

Introduction

Let’s be real - we’ve all been there. You open a codebase that’s been around for a few years, and it’s a mess. Classes doing ten different things, changes breaking stuff in completely unrelated areas, tests that are impossible to write. Sound familiar?

That’s where SOLID principles and Domain-Driven Design (DDD) come in. They’re not just buzzwords people throw around to sound smart. They’re actually practical patterns that help you write code that:

- Doesn’t break when you change something - Modifications stay localized

- Can actually be tested - Each piece works independently

- Makes sense when you read it - Code reflects business logic clearly

- Grows with your project - Adding features doesn’t require massive rewrites

This guide goes deep into both concepts with real .NET examples you can actually use.

SOLID Principles

SOLID is an acronym for five design principles that Uncle Bob (Robert C. Martin) popularized. Don’t let the fancy name intimidate you - these are just common-sense guidelines for writing better code.

Let’s break them down one by one.

1. Single Responsibility Principle (SRP)

A class should have one, and only one, reason to change.

In plain English: Each class should do ONE thing and do it well. If you’re describing what a class does and you use the word “and” - you’ve probably got a problem.

Think of it like a restaurant. You wouldn’t want your chef to also be your accountant and janitor, right? Same principle applies to classes.

Bad Example - Class doing too many things:

public class User

{

public string Name { get; set; }

public string Email { get; set; }

// Violates SRP - User shouldn't handle email sending

public void SendWelcomeEmail()

{

var smtpClient = new SmtpClient("smtp.gmail.com");

var message = new MailMessage

{

To = Email,

Subject = "Welcome!",

Body = $"Welcome {Name}!"

};

smtpClient.Send(message);

}

// Violates SRP - User shouldn't handle database operations

public void SaveToDatabase()

{

using var connection = new SqlConnection("...");

var command = new SqlCommand($"INSERT INTO Users...", connection);

command.ExecuteNonQuery();

}

}Good Example - Separated responsibilities:

// Domain entity - Only handles user data and business rules

public class User

{

public Guid Id { get; private set; }

public string Name { get; private set; }

public string Email { get; private set; }

public User(string name, string email)

{

if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(name))

throw new ArgumentException("Name is required");

if (!IsValidEmail(email))

throw new ArgumentException("Invalid email format");

Id = Guid.NewGuid();

Name = name;

Email = email;

}

private bool IsValidEmail(string email)

{

// Email validation logic

return email.Contains("@");

}

}

// Separate class for email operations

public class EmailService

{

private readonly ISmtpClient _smtpClient;

public EmailService(ISmtpClient smtpClient)

{

_smtpClient = smtpClient;

}

public async Task SendWelcomeEmail(User user)

{

var message = new EmailMessage

{

To = user.Email,

Subject = "Welcome!",

Body = $"Welcome {user.Name}!"

};

await _smtpClient.SendAsync(message);

}

}

// Separate class for database operations

public class UserRepository

{

private readonly DbContext _context;

public UserRepository(DbContext context)

{

_context = context;

}

public async Task SaveAsync(User user)

{

await _context.Users.AddAsync(user);

await _context.SaveChangesAsync();

}

}Real-world benefit: If you need to change how emails are sent (switch from SMTP to SendGrid), you only modify EmailService. The User class remains untouched.

2. Open/Closed Principle (OCP)

Software entities should be open for extension, but closed for modification.

In plain English: You should be able to add new features without changing existing code. Sounds impossible? That’s what interfaces and polymorphism are for.

Bad Example - Must modify class for each new type:

public class PriceCalculator

{

public decimal Calculate(Product product, string customerType)

{

decimal price = product.Price;

// Every new customer type requires modifying this class

if (customerType == "Regular")

{

return price;

}

else if (customerType == "Premium")

{

return price * 0.9m; // 10% discount

}

else if (customerType == "VIP")

{

return price * 0.8m; // 20% discount

}

else if (customerType == "Employee")

{

return price * 0.5m; // 50% discount

}

return price;

}

}Good Example - Extensible through interfaces:

// Abstraction

public interface IDiscountStrategy

{

decimal ApplyDiscount(decimal price);

}

// Different implementations - can add more without changing existing code

public class RegularCustomerDiscount : IDiscountStrategy

{

public decimal ApplyDiscount(decimal price) => price;

}

public class PremiumCustomerDiscount : IDiscountStrategy

{

public decimal ApplyDiscount(decimal price) => price * 0.9m;

}

public class VIPCustomerDiscount : IDiscountStrategy

{

public decimal ApplyDiscount(decimal price) => price * 0.8m;

}

public class EmployeeDiscount : IDiscountStrategy

{

public decimal ApplyDiscount(decimal price) => price * 0.5m;

}

// Closed for modification, open for extension

public class PriceCalculator

{

private readonly IDiscountStrategy _discountStrategy;

public PriceCalculator(IDiscountStrategy discountStrategy)

{

_discountStrategy = discountStrategy;

}

public decimal Calculate(Product product)

{

return _discountStrategy.ApplyDiscount(product.Price);

}

}

// Usage

var regularCalc = new PriceCalculator(new RegularCustomerDiscount());

var vipCalc = new PriceCalculator(new VIPCustomerDiscount());Real-world benefit: Need a new “StudentDiscount”? Just create a new class implementing IDiscountStrategy. No existing code changes needed!

3. Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP)

Derived classes must be substitutable for their base classes.

In plain English: If you have a class that inherits from another class, you should be able to swap them without breaking anything. If you can’t, your inheritance is wrong.

This one trips people up because the classic Rectangle/Square example seems to make sense at first… until it doesn’t.

Bad Example - Violates expectations:

public class Rectangle

{

public virtual int Width { get; set; }

public virtual int Height { get; set; }

public int CalculateArea() => Width * Height;

}

// Square violates LSP

public class Square : Rectangle

{

public override int Width

{

get => base.Width;

set

{

base.Width = value;

base.Height = value; // Side effect!

}

}

public override int Height

{

get => base.Height;

set

{

base.Width = value; // Side effect!

base.Height = value;

}

}

}

// This breaks!

void TestRectangle(Rectangle rect)

{

rect.Width = 5;

rect.Height = 10;

// Expected: 50

// But if rect is Square: 100 (broken!)

Console.WriteLine(rect.CalculateArea());

}Good Example - Proper abstraction:

public interface IShape

{

int CalculateArea();

}

public class Rectangle : IShape

{

public int Width { get; set; }

public int Height { get; set; }

public int CalculateArea() => Width * Height;

}

public class Square : IShape

{

public int Side { get; set; }

public int CalculateArea() => Side * Side;

}

// Works correctly for all shapes

void TestShape(IShape shape)

{

Console.WriteLine(shape.CalculateArea());

}Real-world benefit: Your code works predictably regardless of which implementation is used at runtime.

4. Interface Segregation Principle (ISP)

Clients should not be forced to depend on interfaces they don’t use.

In plain English: Don’t create fat interfaces that force classes to implement methods they don’t need. Better to have many small, focused interfaces than one giant one.

Think of it like a TV remote. You don’t want a universal remote with 500 buttons when you only use 10. Same with interfaces.

What it means: Many small, specific interfaces are better than one large, general-purpose interface.

Bad Example - Fat interface:

// Forces all implementations to have methods they don't need

public interface IWorker

{

void Work();

void Eat();

void Sleep();

void GetPaid();

}

// Robot doesn't eat or sleep!

public class Robot : IWorker

{

public void Work() { /* ... */ }

public void Eat()

{

// Forced to implement but doesn't make sense

throw new NotImplementedException();

}

public void Sleep()

{

// Forced to implement but doesn't make sense

throw new NotImplementedException();

}

public void GetPaid()

{

throw new NotImplementedException();

}

}Good Example - Segregated interfaces:

public interface IWorkable

{

void Work();

}

public interface IFeedable

{

void Eat();

}

public interface ISleepable

{

void Sleep();

}

public interface IPayable

{

void GetPaid();

}

// Human needs everything

public class Human : IWorkable, IFeedable, ISleepable, IPayable

{

public void Work() { /* ... */ }

public void Eat() { /* ... */ }

public void Sleep() { /* ... */ }

public void GetPaid() { /* ... */ }

}

// Robot only implements what it needs

public class Robot : IWorkable

{

public void Work() { /* ... */ }

}

// Manager can work with specific contracts

public class WorkManager

{

public void ManageWorker(IWorkable worker)

{

worker.Work();

}

public void ManageBreak(IFeedable feedable)

{

feedable.Eat();

}

}Real-world benefit: Classes only depend on methods they actually use, making the codebase more flexible and maintainable.

5. Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP)

High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules. Both should depend on abstractions.

In plain English: Depend on interfaces/abstractions, not concrete implementations. This is probably the MOST important principle for Clean Architecture.

Here’s why it matters: when your business logic depends directly on database code or external services, you’re stuck. Can’t test without a database, can’t swap implementations, can’t do anything without breaking everything.

Bad Example - Direct dependency on implementation:

// High-level business logic

public class OrderService

{

// Directly depends on concrete implementation

private readonly SqlServerDatabase _database;

private readonly SmtpEmailService _emailService;

public OrderService()

{

_database = new SqlServerDatabase(); // Tight coupling!

_emailService = new SmtpEmailService(); // Tight coupling!

}

public void PlaceOrder(Order order)

{

_database.Save(order);

_emailService.SendConfirmation(order.CustomerEmail);

}

}Good Example - Depends on abstractions:

// Abstractions (interfaces)

public interface IDatabase

{

void Save(Order order);

}

public interface IEmailService

{

void SendConfirmation(string email);

}

// High-level business logic depends on abstractions

public class OrderService

{

private readonly IDatabase _database;

private readonly IEmailService _emailService;

// Dependencies injected via constructor

public OrderService(IDatabase database, IEmailService emailService)

{

_database = database;

_emailService = emailService;

}

public void PlaceOrder(Order order)

{

_database.Save(order);

_emailService.SendConfirmation(order.CustomerEmail);

}

}

// Low-level implementations

public class SqlServerDatabase : IDatabase

{

public void Save(Order order) { /* SQL Server specific */ }

}

public class MongoDatabase : IDatabase

{

public void Save(Order order) { /* MongoDB specific */ }

}

public class SmtpEmailService : IEmailService

{

public void SendConfirmation(string email) { /* SMTP specific */ }

}

public class SendGridEmailService : IEmailService

{

public void SendConfirmation(string email) { /* SendGrid specific */ }

}

// Wiring up with Dependency Injection

services.AddScoped<IDatabase, SqlServerDatabase>();

services.AddScoped<IEmailService, SendGridEmailService>();

services.AddScoped<OrderService>();Real-world benefit: Switch from SQL Server to MongoDB? Change from SMTP to SendGrid? Just change the DI registration. OrderService code remains unchanged!

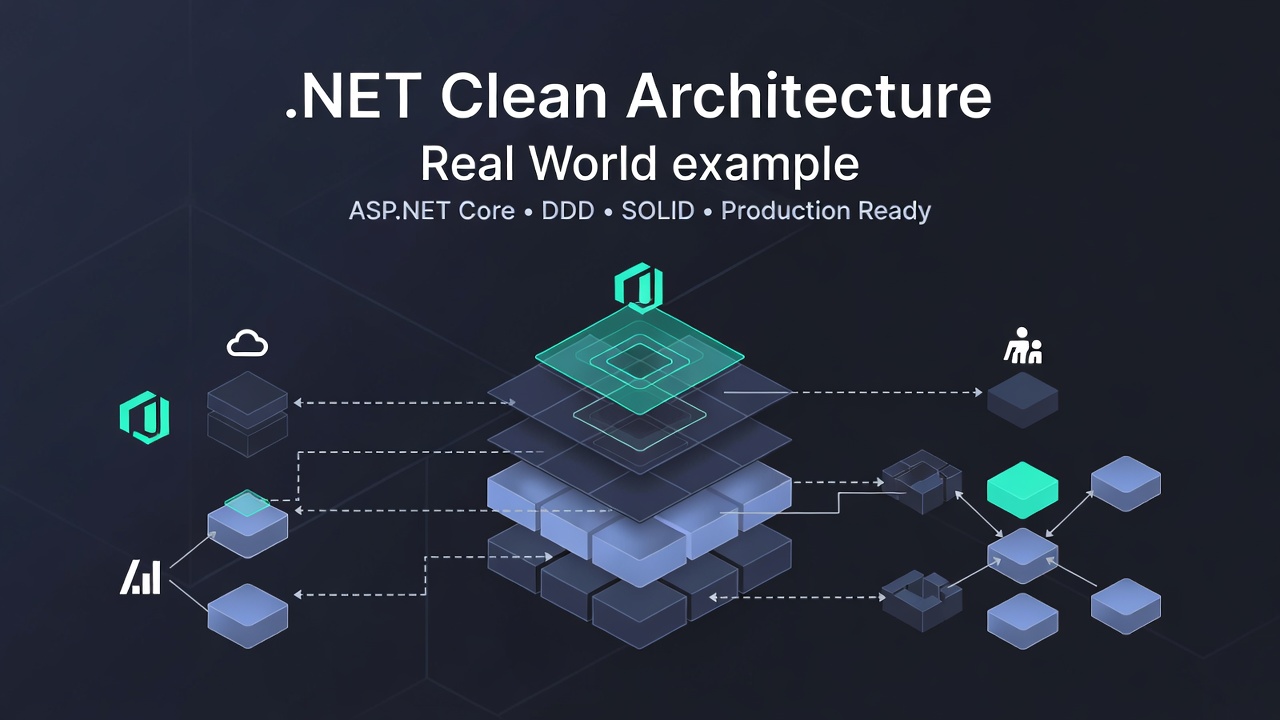

Domain-Driven Design (DDD)

Alright, now let’s talk about Domain-Driven Design. If SOLID principles are about how to write good code, DDD is about how to model your business logic.

DDD comes from Eric Evans’ book and it’s all about making your code reflect the real-world business domain. Not your database schema, not your API endpoints - the actual business logic and rules.

Core Concepts

Here are the main building blocks you need to know:

1. Entities

What: Objects with unique identity that persists over time.

Characteristics:

- Have a unique identifier (ID)

- Identity remains constant even if properties change

- Contain business logic and rules

- Protect invariants

Example:

public class Order

{

// Unique identity

public Guid Id { get; private set; }

// Properties that can change

public OrderStatus Status { get; private set; }

public DateTime OrderDate { get; private set; }

public decimal TotalAmount { get; private set; }

// Collection of order items

private readonly List<OrderItem> _items = new();

public IReadOnlyCollection<OrderItem> Items => _items.AsReadOnly();

// Factory method ensures valid creation

public static Order Create(Guid customerId)

{

return new Order

{

Id = Guid.NewGuid(),

CustomerId = customerId,

OrderDate = DateTime.UtcNow,

Status = OrderStatus.Pending

};

}

// Business logic encapsulated in entity

public void AddItem(Product product, int quantity)

{

if (Status != OrderStatus.Pending)

throw new InvalidOperationException("Cannot add items to non-pending order");

if (quantity <= 0)

throw new ArgumentException("Quantity must be positive");

var item = new OrderItem(product, quantity);

_items.Add(item);

TotalAmount += item.Price * quantity;

}

public void Submit()

{

if (_items.Count == 0)

throw new InvalidOperationException("Cannot submit empty order");

Status = OrderStatus.Submitted;

}

public void Cancel()

{

if (Status == OrderStatus.Delivered)

throw new InvalidOperationException("Cannot cancel delivered order");

Status = OrderStatus.Cancelled;

}

}Real-world: An order with ID “12345” remains the same order even if items are added or status changes.

2. Value Objects

What: Objects defined by their values, not identity. Two value objects with the same values are considered equal.

Characteristics:

- Immutable (cannot be changed after creation)

- No unique identifier needed

- Compared by value, not reference

- Validate on creation

Example:

public class Address : ValueObject

{

public string Street { get; }

public string City { get; }

public string State { get; }

public string ZipCode { get; }

public string Country { get; }

public Address(string street, string city, string state, string zipCode, string country)

{

// Validation

if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(street))

throw new ArgumentException("Street is required");

if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(city))

throw new ArgumentException("City is required");

Street = street;

City = city;

State = state;

ZipCode = zipCode;

Country = country;

}

// Value objects are compared by value

protected override IEnumerable<object> GetEqualityComponents()

{

yield return Street;

yield return City;

yield return State;

yield return ZipCode;

yield return Country;

}

// Provide meaningful behavior

public string GetFullAddress()

{

return $"{Street}, {City}, {State} {ZipCode}, {Country}";

}

}

// Base class for value objects

public abstract class ValueObject

{

protected abstract IEnumerable<object> GetEqualityComponents();

public override bool Equals(object obj)

{

if (obj == null || obj.GetType() != GetType())

return false;

var other = (ValueObject)obj;

return GetEqualityComponents()

.SequenceEqual(other.GetEqualityComponents());

}

public override int GetHashCode()

{

return GetEqualityComponents()

.Select(x => x?.GetHashCode() ?? 0)

.Aggregate((x, y) => x ^ y);

}

}Real-world: “123 Main St, New York” is the same address regardless of which customer has it. No need for an AddressId.

3. Aggregates

What: A cluster of domain objects (entities and value objects) that can be treated as a single unit.

Characteristics:

- Has an Aggregate Root (main entity)

- Enforces business rules across all objects in the aggregate

- External objects can only reference the aggregate root

- Changes saved/loaded as a unit

Example:

// Order is the Aggregate Root

public class Order

{

public Guid Id { get; private set; }

public Guid CustomerId { get; private set; }

public Address ShippingAddress { get; private set; }

public OrderStatus Status { get; private set; }

// Encapsulated collection - can't be modified directly from outside

private readonly List<OrderItem> _items = new();

public IReadOnlyCollection<OrderItem> Items => _items.AsReadOnly();

// Aggregate root controls all changes

public void AddItem(Product product, int quantity)

{

// Business rule: Can't add to non-pending orders

if (Status != OrderStatus.Pending)

throw new InvalidOperationException("Cannot modify non-pending order");

// Business rule: Total items can't exceed 50

if (_items.Count >= 50)

throw new InvalidOperationException("Order cannot have more than 50 items");

var existingItem = _items.FirstOrDefault(i => i.ProductId == product.Id);

if (existingItem != null)

{

existingItem.IncreaseQuantity(quantity);

}

else

{

_items.Add(new OrderItem(product.Id, product.Name, product.Price, quantity));

}

}

public void RemoveItem(Guid productId)

{

if (Status != OrderStatus.Pending)

throw new InvalidOperationException("Cannot modify non-pending order");

var item = _items.FirstOrDefault(i => i.ProductId == productId);

if (item != null)

{

_items.Remove(item);

}

}

public decimal GetTotalAmount()

{

return _items.Sum(i => i.Price * i.Quantity);

}

}

// OrderItem is part of the Order aggregate

// Not accessible directly - only through Order

public class OrderItem

{

public Guid ProductId { get; private set; }

public string ProductName { get; private set; }

public decimal Price { get; private set; }

public int Quantity { get; private set; }

internal OrderItem(Guid productId, string productName, decimal price, int quantity)

{

if (quantity <= 0)

throw new ArgumentException("Quantity must be positive");

ProductId = productId;

ProductName = productName;

Price = price;

Quantity = quantity;

}

internal void IncreaseQuantity(int amount)

{

if (amount <= 0)

throw new ArgumentException("Amount must be positive");

Quantity += amount;

}

}Real-world: An order with its items is like a shopping cart - you don’t add items directly to the database, you add them through the cart (aggregate root).

4. Domain Events

What: Something important that happened in the domain that other parts of the system might care about.

Characteristics:

- Immutable (happened in the past)

- Named in past tense

- Contain all relevant data

- Used for decoupling and eventual consistency

Example:

// Base interface for domain events

public interface IDomainEvent

{

Guid EventId { get; }

DateTime OccurredOn { get; }

}

// Specific domain events

public class OrderPlacedEvent : IDomainEvent

{

public Guid EventId { get; } = Guid.NewGuid();

public DateTime OccurredOn { get; } = DateTime.UtcNow;

public Guid OrderId { get; }

public Guid CustomerId { get; }

public decimal TotalAmount { get; }

public List<OrderItemDto> Items { get; }

public OrderPlacedEvent(Guid orderId, Guid customerId, decimal totalAmount, List<OrderItemDto> items)

{

OrderId = orderId;

CustomerId = customerId;

TotalAmount = totalAmount;

Items = items;

}

}

public class OrderCancelledEvent : IDomainEvent

{

public Guid EventId { get; } = Guid.NewGuid();

public DateTime OccurredOn { get; } = DateTime.UtcNow;

public Guid OrderId { get; }

public string Reason { get; }

public OrderCancelledEvent(Guid orderId, string reason)

{

OrderId = orderId;

Reason = reason;

}

}

// Entity raises events

public class Order

{

private readonly List<IDomainEvent> _domainEvents = new();

public IReadOnlyCollection<IDomainEvent> DomainEvents => _domainEvents.AsReadOnly();

public void Submit()

{

// Business logic

if (_items.Count == 0)

throw new InvalidOperationException("Cannot submit empty order");

Status = OrderStatus.Submitted;

// Raise domain event

var items = _items.Select(i => new OrderItemDto(i.ProductId, i.Quantity)).ToList();

_domainEvents.Add(new OrderPlacedEvent(Id, CustomerId, GetTotalAmount(), items));

}

public void Cancel(string reason)

{

if (Status == OrderStatus.Delivered)

throw new InvalidOperationException("Cannot cancel delivered order");

Status = OrderStatus.Cancelled;

// Raise domain event

_domainEvents.Add(new OrderCancelledEvent(Id, reason));

}

public void ClearDomainEvents()

{

_domainEvents.Clear();

}

}

// Event handlers respond to events

public class OrderPlacedEventHandler

{

private readonly IEmailService _emailService;

private readonly IInventoryService _inventoryService;

public async Task Handle(OrderPlacedEvent evt)

{

// Send confirmation email

await _emailService.SendOrderConfirmation(evt.CustomerId, evt.OrderId);

// Reserve inventory

foreach (var item in evt.Items)

{

await _inventoryService.ReserveStock(item.ProductId, item.Quantity);

}

}

}Real-world: When an order is placed, automatically send email, update inventory, notify warehouse - all without tight coupling.

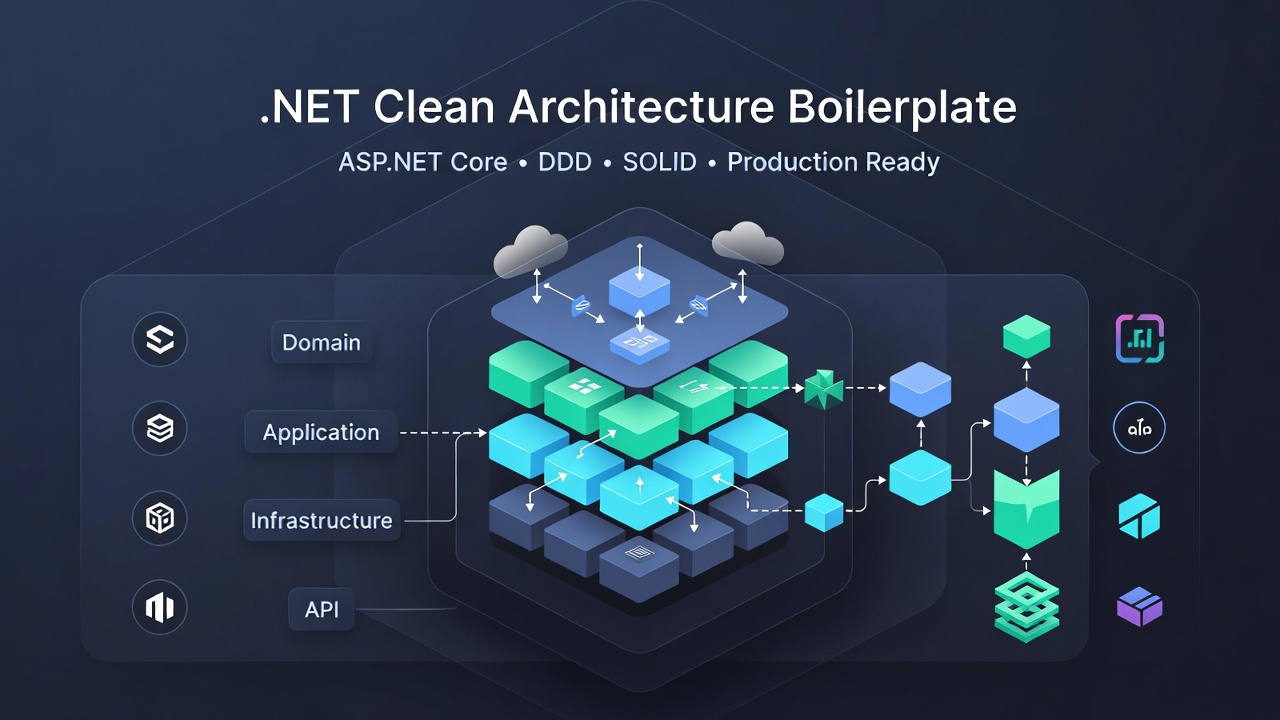

5. Repositories

What: Abstraction for accessing and persisting aggregates. Acts like an in-memory collection.

Characteristics:

- One repository per aggregate root

- Hides database implementation details

- Provides collection-like interface

- Defined in Domain/Application layer, implemented in Infrastructure

Example:

// Interface in Application/Domain layer

public interface IOrderRepository

{

Task<Order> GetByIdAsync(Guid id);

Task<List<Order>> GetByCustomerIdAsync(Guid customerId);

Task<List<Order>> GetPendingOrdersAsync();

Task AddAsync(Order order);

Task UpdateAsync(Order order);

Task DeleteAsync(Order order);

}

// Implementation in Infrastructure layer

public class OrderRepository : IOrderRepository

{

private readonly DbContext _context;

public OrderRepository(DbContext context)

{

_context = context;

}

public async Task<Order> GetByIdAsync(Guid id)

{

return await _context.Orders

.Include(o => o.Items)

.FirstOrDefaultAsync(o => o.Id == id);

}

public async Task<List<Order>> GetByCustomerIdAsync(Guid customerId)

{

return await _context.Orders

.Include(o => o.Items)

.Where(o => o.CustomerId == customerId)

.OrderByDescending(o => o.OrderDate)

.ToListAsync();

}

public async Task<List<Order>> GetPendingOrdersAsync()

{

return await _context.Orders

.Include(o => o.Items)

.Where(o => o.Status == OrderStatus.Pending)

.ToListAsync();

}

public async Task AddAsync(Order order)

{

await _context.Orders.AddAsync(order);

}

public async Task UpdateAsync(Order order)

{

_context.Orders.Update(order);

}

public async Task DeleteAsync(Order order)

{

_context.Orders.Remove(order);

}

}

// Usage in Application layer

public class PlaceOrderHandler

{

private readonly IOrderRepository _orderRepository;

private readonly IUnitOfWork _unitOfWork;

public async Task<Guid> Handle(PlaceOrderCommand command)

{

// Use repository like an in-memory collection

var order = Order.Create(command.CustomerId);

foreach (var item in command.Items)

{

order.AddItem(item.Product, item.Quantity);

}

order.Submit();

await _orderRepository.AddAsync(order);

await _unitOfWork.SaveChangesAsync();

return order.Id;

}

}Real-world: Repository hides whether data is stored in SQL Server, MongoDB, or memory - business logic doesn’t care!

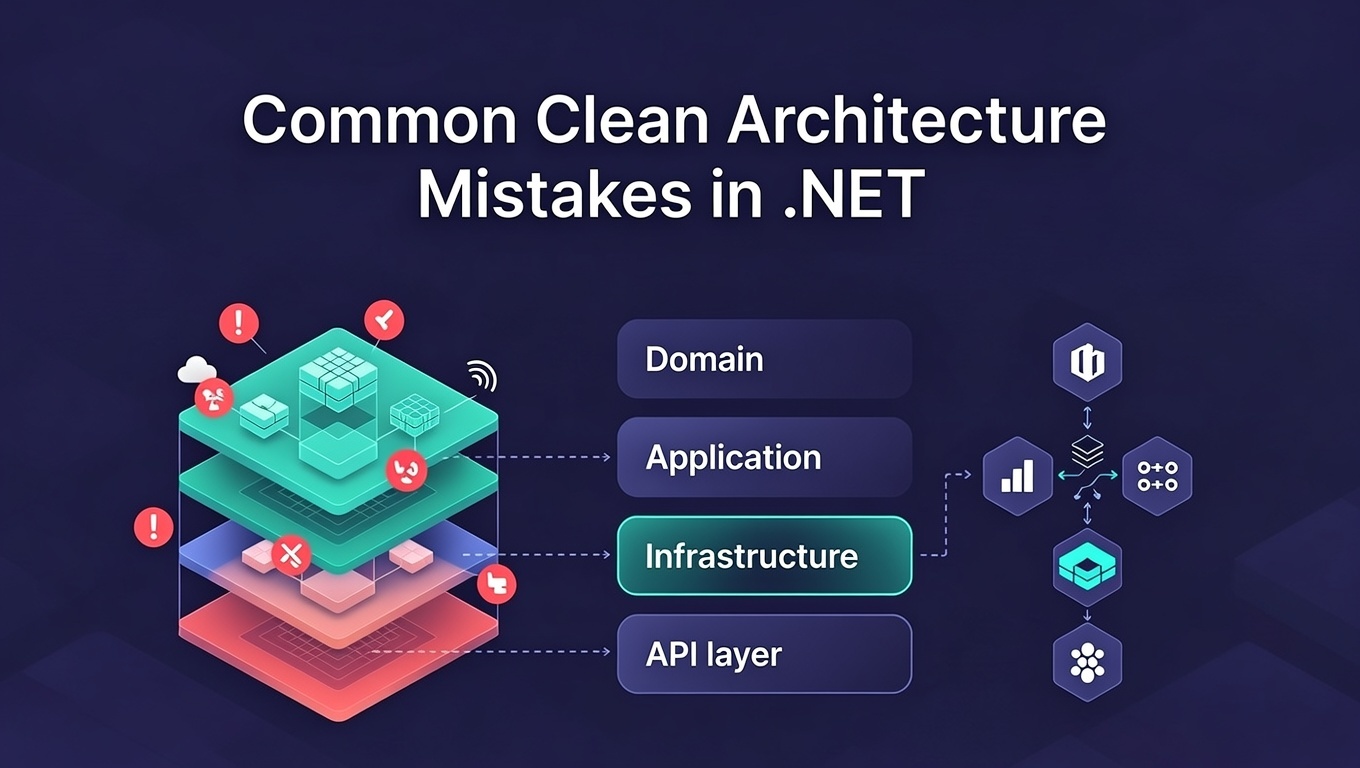

How SOLID and DDD Work Together

SOLID principles and DDD complement each other perfectly:

| SOLID Principle | DDD Application |

|---|---|

| SRP | Entities have single business concept, repositories handle only persistence |

| OCP | Domain events allow extending behavior without modifying core domain |

| LSP | Value objects and entities can be substituted where their base types are expected |

| ISP | Repositories expose only methods needed for that aggregate |

| DIP | Domain depends on repository interfaces, not implementations |

Example showing both:

// DDD: Domain Event

public class ProductPriceChangedEvent : IDomainEvent { }

// DDD: Entity with SOLID principles

public class Product // SRP: Only handles product logic

{

public void UpdatePrice(Money newPrice) // DIP: Depends on Money abstraction

{

// Business rule validation

if (newPrice.Amount <= 0)

throw new DomainException("Price must be positive");

var oldPrice = Price;

Price = newPrice;

// Domain event for extensibility (OCP)

AddDomainEvent(new ProductPriceChangedEvent(Id, oldPrice, newPrice));

}

}

// ISP: Specific interface for product operations

public interface IProductRepository

{

Task<Product> GetByIdAsync(Guid id);

Task UpdateAsync(Product product);

}Best Practices Summary

SOLID Best Practices

- Keep classes small and focused (SRP)

- Use interfaces and abstract classes (OCP, DIP)

- Avoid breaking derived class contracts (LSP)

- Create role-specific interfaces (ISP)

- Inject dependencies (DIP)

DDD Best Practices

- Model the domain accurately - Talk to domain experts

- Use ubiquitous language - Same terms in code and business discussions

- Protect invariants - Validate in entity constructors and methods

- Keep aggregates small - Only include what must be consistent together

- Use domain events - For decoupling and side effects

- Make value objects immutable - Easier to reason about and test

Further Reading

- Book: “Domain-Driven Design” by Eric Evans

- Book: “Clean Architecture” by Robert C. Martin

- Book: “Implementing Domain-Driven Design” by Vaughn Vernon

- Article: SOLID Principles in C#

Wrapping Up

Look, I get it - this is a LOT of information. SOLID principles, entities, value objects, aggregates, repositories… it can feel overwhelming.

But here’s the thing: you don’t need to implement all of this perfectly from day one. Start small:

- Pick one principle - Maybe start with SRP. Just try to make each class do one thing

- Apply it to new code first - Don’t refactor your entire codebase overnight

- Learn from mistakes - You’ll violate these principles. That’s fine. You’ll learn what works

- Gradually improve - As you get comfortable, add more patterns

The goal isn’t to create “perfect” code. It’s to write code that:

- You can understand six months from now

- Your teammates can work with

- Can evolve as business requirements change

- Can actually be tested

These patterns exist because developers kept making the same mistakes over and over. Learn from their pain, avoid those mistakes yourself.

Got questions? Disagree with something? Drop a comment. I’d love to hear about your experiences with these patterns. Happy coding! 🚀